Perhaps you remember the “But wait! There’s more!” line from the Ginsu knife ads. Or maybe you recall anxiously searching for the “prize” in the cereal box. Companies often add special “free” features to enhance the perceived value of their products. Similarly, pharma/biotech and medtech manufacturers offer value-added services — patient and provider education, disease management programs, and patient assistance programs are common examples. From the payer’s perspective, some of these “companion services,” as we will call them, add value to the product, while others subtract value.

When value is added

When a manufacturer-sponsored service lowers payers’ costs, it adds value. But payers need to believe this is the case, and their beliefs typically are rooted in experience or evidence. It is not enough for a manufacturer to say, for example, that a service can boost patient or provider adherence. Payers may rely on previous experience with similar promises when considering the merits of the offer. Or, when an intermediate outcome like improved adherence aligns with a payer’s goals or yields other benefits it values (e.g., lower costs, greater member satisfaction, or higher performance on reporting measures, particularly those associated with financial incentives and disincentives), a payer may welcome evidence that the service can actually move the needle.

For example, some medications are associated with medical cost offsets. Payers want their members to take these medications, and patient assistance programs can help some patients afford them. When lack of affordability has a negative impact on adherence, then payers welcome manufacturer support. Other manufacturer-led support services can help some patients use products correctly or work through issues associated with the condition and/or the product, avoiding inadvertent misuse of the product or unmanaged problems like side effects that can generate additional costs. In these cases, payers think supportive services can truly add value.

When value is subtracted

When payers don’t think a manufacturer-sponsored companion service adds value, then, by definition, it subtracts value. Huh? To payers, the cost of an unwanted service would be better used to lower the product’s acquisition cost. And when payers value a service but prefer to build or buy a similar service, then the manufacturer-sponsored service subtracts value. This is especially true if the payer believes its own build or buy options are more impactful and/or bias-free.

Even when payers value a service and appreciate that a manufacturer adds it to the product offer, things can still go south during implementation. Something that should be relatively simple, like re-ordering materials, may look good on paper, but if it creates delays and causes frustration, a manufacturer’s hard-earned trust can be quickly lost. Payers have an easier time recalling manufacturers’ failures than their successes. Not surprisingly, trust in a manufacturer can encourage adoption of a value-added service, but prior adoption is needed to build trust — a chicken-and-egg problem for manufacturers.

When payers value a companion service and it is implemented well, then value can still be subtracted when the service is discontinued, particularly if support ends sooner than expected. Tennyson’s adage “’Tis better to have loved and lost than never have loved at all” is at odds with some empirical evidence. Consider a study that showed that nursing home patients who were given a plant to care for or who had regular interaction with an animal had better outcomes than a control group without these benefits. However, a follow-up study of the same population showed that after the experiment ended and lost the added benefits, outcomes for the treatment group were worse than both their baseline and the control group! Payers are generally risk averse and will shy away from services with uncertain sustainability.

And to be clear, even when a payer believes a companion service works as intended by the manufacturer, misalignment with a payer’s goals will result in rejection. If, for instance, the service increases utilization when the payer’s goal is to decrease utilization, then in the eyes of the payer, the service subtracts value. The same is true if the payer has a fundamental dislike of the product — if so, then the payer won’t like the companion service, either.

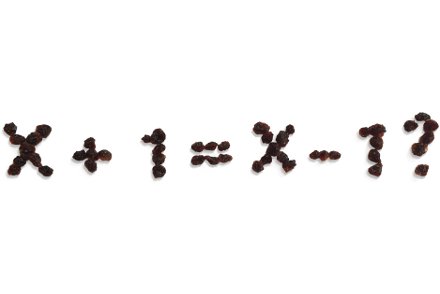

A balanced equation

Manufacturers need to identify which services a payer wants, and which of those they want from manufacturers. If a payer is open to a manufacturer-provided service, manufacturers then need to figure out how to build and execute it in a way that meets the payer’s needs and measure its success in a convincing way.

Alternatively, manufacturers can keep it a bit simpler by bringing to market products that payers value (versus me-toos), providing convincing evidence of the clinical and economic value of their products, and pricing products fairly based on their value. Payers are savvy enough to know when a companion service is being fronted as a substitute for lack of these attributes.

In general, payers simply want manufacturers to focus on their core products and not value-added services. That said, real-world use of some products can produce failures that manufacturers can help to address, providing welcomed opportunities to enhance the value of those products. Payers’ valuations of products can be challenging, and adding a companion service to the mix can complicate these valuations. Here and elsewhere, payers are curators of manufacturers’ offers, selecting some and rejecting others based on somewhat predictable criteria interacting with the market context.

No Comments