If you’ve experienced the joy of attending the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, you know that the balloons are huge. The new Astronaut Snoopy, for instance, is 49 feet tall, 43 feet long, 29 feet wide, and requires 90 handlers. Seeing the inflated balloons or watching them be inflated is a swell time.

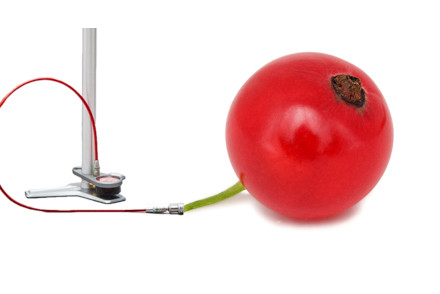

But not all things inflated are filled with joy. The rising price of drugs has captured the nation’s attention, and public discourse is full of proposals on how to reverse this trend. One method for slowing inflation that can be found in most rebate contracts is referred to as price protection.

Stretching the truth

Twenty-five years ago, health economist Joseph Newhouse argued that innovation (i.e., new technology with enhanced capabilities) was the main driver of increasing healthcare spend, not other factors like the aging population, defensive medicine, rising administrative costs, spending on the terminally ill, or lagging productivity. Fast forward: New technologies, like gene therapies, are now entering the market at higher prices never seen before. For example, Zolgensma costs $2.1 million — and may be worth every penny if its effect is durable. But new technology is not the only source of higher prices.

More recently, University of Pittsburgh researchers found that while the rising costs of generic and specialty drugs were driven mostly by new, more expensive products entering the market, the rising costs of branded drugs were mostly due to price inflation for drugs already on the market. These results showed that price inflation for oral and injectable branded products averaged 8 percent and 16 percent, respectively, which was five to eight times the general rate of inflation during the same time period.

Manufacturers often point to the costs and risks of drug development. Fair enough. Manufacturers and their investors should charge an amount that covers their costs, including the many failures that don’t make it to market. And the amount charged should yield an attractive ROI that motivates the innovation the market demands.

However, price increases that outpace the general inflation rate are less defensible. So, why do some manufacturers increase prices at rates that seem excessive? The simple answer is: Because they can. Most increases escape attention, although some truly egregious increases make news. Perhaps most infamous was Turing Pharmaceuticals’ 5,456% price increase for Daraprim, a drug available since 1953. Even if you don’t recall the company or the drug, you probably remember the smirking face of Martin Shkreli, the greedy CEO behind that price hike.

Leonard Schleifer, founder and CEO of Regeneron, said in 2016 that “we as an industry have used price increases to cover up the gaps in innovation.” He went on to say that “if you look at the prices of drugs, they have gone up, sometimes [by] double digits twice a year, as a very efficient way of increasing profits without coupled to any innovation.”

How payers pump the brakes

Price protection can successfully slow price inflation and has become a standard feature of payers’ contracts with manufacturers. Negotiated terms vary in metrics, timeframes, thresholds, and rebates, but at their core a rebate offsets price increases exceeding an agreed upon amount. The threshold can be fixed for multiple years or change each year — and if it changes, negotiated rules limit these increases. Price protection is also a feature of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program that similarly requires manufacturers to pay a rebate for price increases that exceed inflation.

While this form of contracting can bend the cost curve for some products, price increases for other products remain untouched. When there’s no contracting, there’s no price protection. And when there’s no competition or when there is little to no management due to a lack of evidence or support, there’s little to no contracting. Think rare diseases, novel specialty products, and oncology. So, the utility of price protection has limits.

A recent study by the Kaiser Family Foundation looked the list price of drugs covered by Medicare Part D between 2016 and 2017 and found that for 60% of them, price increases exceeded the inflation rate. Twenty of the top 25 drugs that accounted for the largest spend exceeded the inflation rate, with some experiencing double-digit increases. Medicare is forbidden by law to negotiate drug prices with manufacturers, but given overwhelming political support, that is likely to change soon. And if it does, we’ll surely see CMS start to use price protection in its contracts with manufacturers.

Blowing up value

The value equation tells us that the value of a product is, in part, determined by its cost. In general, when the cost inflates, the perceived value deflates — although this general rule breaks down for some products and services when premium pricing enhances the perceived value (e.g., exclusive luxury brands). Presumably manufacturers understand that payers and other access decision makers associate price increases with diminishing value. And this may, in part, explain parallel efforts by manufacturers to develop real-world evidence that enhances the value. In the absence of price protection, payers experiencing an egregious price increase may have to bide their time until sufficient competition, evidence, or legal or societal support permits them to restrict access.

While it takes 90 minutes to inflate giant balloons like Snoopy, it only takes about 15 minutes to deflate them. High and sometimes very high prices for new innovative products can be fair, but high price increases can instantly suck the value from an existing product that took many years to grow.

No Comments