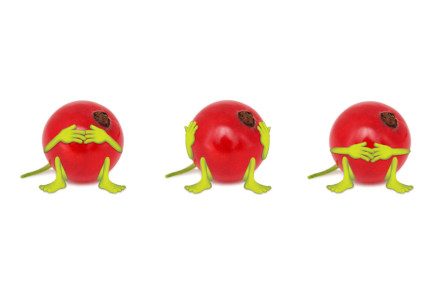

The three “wise monkeys” depicted in a 17th century wood carving at the Tosho-gu shrine in Nikko, Japan, represent the proverb “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil.” This proverb is likely rooted in a much more ancient code of conduct by Confucius: Look not at what is contrary to propriety; listen not to what is contrary to propriety; speak not what is contrary to propriety; make no movement that is contrary to propriety.

In exchange for market access, drug manufacturers offer payers confidential contracts that, in essence, charge different customers different amounts. Economists impartially refer to this as price discrimination and consider it a rational attempt by sellers to capture some of the consumer surplus and increase their economic profit. Yet a rising chorus of observers sees only impropriety in these secretive deals. Despite the controversy, such contracting and contractual prohibitions on disclosing contract terms are the norm.

See no evil

Manufacturers, PBMs, and MCOs do not see the impropriety of proprietary contracting — these secret rebates and discounts are accepted as standard practice and viewed as good business. Manufacturers use contracting to maximize revenues, whereas PBMs and MCOs use contracting to minimize costs. On both sides, these stakeholders use contracting to maximize profits. This bilateral pursuit, shrouded in secrecy, fosters competition. Here, the ideals of transparency and competition are interestingly at odds.

PBMs often offer MCOs (and self-insured employers) attractive rebate guarantees. These guarantees yield even greater savings than what an MCO might achieve through direct contract negotiations with manufacturers. When an MCO outsources contracting to a PBM, it becomes detached from the contract and may lose access to and/or interest in the contract. If an MCO gets the rebate guarantee it wants, then the contract may lose importance when viewed simply as a means to savings.

Speak no evil

Manufacturers, PBMs, and MCOs share a desire to keep proprietary contracts confidential because each has competitors. Manufacturers do not want the terms they offer a payer shared with other payers and competing manufacturers. Similarly, payers do not want competing payers to know the terms they accept. To ensure alignment on this goal, payers are contractually obligated not to tell other manufacturers or payers about their contracts.

Medicaid’s payment for covered outpatient drugs is based on manufacturers’ “best price” — the lowest prices that manufacturers charge any wholesaler, retailer, provider, health plan, not-for-profit, or governmental entity, with some important exceptions, including the VA, the Department of Defense, and organizations eligible to participate in the 340B drug program. Section 1927 of the Social Security Act details how payments are calculated and the information that manufacturers must report to CMS. Importantly, the product-specific prices manufacturers report are confidential, and the Act makes it clear that these prices cannot be disclosed by federal and state agencies (and their contractors). For competitive-intelligence reasons, manufacturers and commercial payers alike would love to hear about the best deals in the market, but can’t — not even through a Freedom of Information Act request. Federal law keeps manufacturers’ “best price” a best-kept secret. Remarkably, there have been no reports of leaks over the years.

Hear no evil

If a payer were to know about the secret deals other payers get from a manufacturer, then it would likely request or even demand the same terms. Despite not hearing about competitors’ agreements, most payers believe the terms they achieve are competitive! Of course, that’s hard to prove or disprove.

Self-insured employers do not hear about negotiated rebates and discounts. These employers (more likely, their consultants) may ask for this information or attempt to audit it, but the rebates and contracts are closely guarded trade secrets. Plan sponsors are told only what they truly want to hear — that their premiums are managed and their guaranteed rebate savings are maximized.

Do no evil

Some depictions of the so-called “wise monkeys” add a fourth “do no evil” monkey to round out Confucius’s code of conduct. Payers readily recognize problems inextricably tied to confidential contracts.

First, the lack of transparency obfuscates the net cost and hampers public efforts like those by ICER to measure and compare value. Payers may attempt to leverage assessments of cost effectiveness by ICER and other HTAs when negotiating contracts with manufacturers. But the lack of transparency of the true net cost of products negatively impacts the validity of these assessments and, as a result, the utility of these assessments during contract negotiations.

Second, manufacturers are incentivized to raise list prices and offer larger rebates so that PBMs can deliver on their rebate-savings guarantees. This vicious cycle has an unfortunate inflationary effect on list prices. List-price inflation raises retail pharmacy prices, and because coinsurance is typically based on retail prices, out-of-pocket costs go up for patients with coinsurance unless they have a point-of-sale rebate plan. But point-of-sale rebate plans are neither common nor a simple fix to this problem, because offering such a plan would increase premiums. Under point-of-sale rebate plans, some patients may win (although how many and how much is unclear), while others would certainly lose. List price inflation clearly hurts patients with no drug coverage.

But simply banning confidential rebates, as some have suggested, is a naïve potential fix. Confidential discounts would likely replace these rebates, further support price discrimination, and would likely have a similar inflationary effect on list prices. PBMs would likely continue to add value by offering discount guarantees to MCOs and plan sponsors. Unless we move to a single-payer system, confidential contracting, in one form or another, is here to stay.

Visually, it is not easy to represent the “do no evil” monkey. And doing no evil (or harm) is extremely hard to do, and arguably much harder than not seeing, hearing, or speaking evil. Maybe that’s why the fourth monkey is commonly left out of the picture. For those who think getting rid of confidential contracts between manufacturers and PBMs/MCOs will get a monkey off their backs, think again.

No Comments