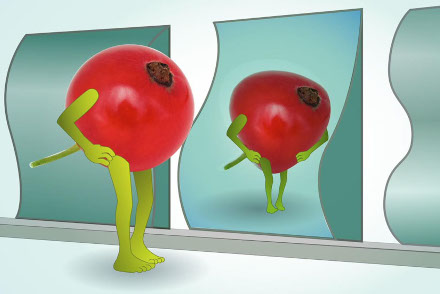

Ever stood in front of a funhouse mirror? The warped reflections transform the way you look — stretching your torso while shrinking your legs, or vice versa. These curved mirrors, with their convex and concave sections, bend reality in amusing ways. But while carnival distortions are harmless, distortions of legislative intent can have serious policy implications.

The 340B drug discount program reflects different images to different viewers. At its core, it’s a program that enables certain health care providers — known as “covered entities” — to purchase drugs at lower costs. These covered entities are primarily large hospitals serving a disproportionate share of low-income patients, along with various federally funded and other safety net providers. The ongoing conflict among stakeholders regarding covered entities’ use of savings (sometimes inaccurately referred to as “profits”) reveals opposing views on the program’s intent.

The legislation

Go on, take a look at the enabling legislation. In Title VI, we see statutory language focusing on technical specifications:

- Defining the rebate percentage

- Describing the applicable drugs

- Defining covered entities

- Prohibiting duplicate discounts/rebates and the resale of drugs

What you won’t see is a single word about how covered entities should use savings — a blind spot that has led to debate about the program’s purpose and left covered entities to make their own determinations about appropriate use of these funds.

And as for the legislative intent, the text of the law provides no line of sight. Many erroneously repeat what others have said — that you can find intent in the statutory language — but it is not there.

Textualists, be they conservative or liberal. interpret legal texts based on their plain and ordinary meaning at the time they were enacted. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia was a prominent advocate of textualism. Justice Elena Kagan said in 2015 “we’re all textualists now” but rescinded this claim in 2022. Divining the intent of legislation is fraught with challenges. Scalia noted that members of Congress could have voted for the legislation for different reasons.

A Congressional report

A House Energy and Commerce committee report (House Report No. 102-384(II)) accompanying the original legislation is very clear about the purpose of the legislation. The first line of the report’s “Purpose and Summary” section reads as follows:

“The purpose of [this legislation] is to enable [covered entities] to obtain lower prices on the drugs that they provide to their patients.”

And buried in the “Background and Need for the Legislation” section, we find a single, familiar line:

“In giving these “covered entities” access to price reductions the Committee intends to enable these entities to stretch scarce Federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.”

Even this committee language — often seen as evidence of Congressional intent — provides no reflection on whether savings should be shared with patients or invested in services. The obtuse language has left covered entities without clear guidance on appropriate uses of savings.

Further, this was presumably the committee’s intent and was not necessarily the intent of Congress. Textualists argue that Congress enacts statutes, not committee reports. Scalia said that the notion you can pluck a statement from a committee report, often not read by the committee much less read by the whole house of Congress and read even less by the other house, is the last surviving fiction in American law.

The federal oversight agency

The Health Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) oversees the 340B drug discount program. How does it view the program’s intent? For what it’s worth, HRSA’s description of the program reflects that line found in the Congression report:

“The 340B Program enables covered entities to stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.”

This likely explains why many descriptions of the program use this language.

The advocates

Advocates of the 340B program typically use HRSA’s text or similar language to describe the program.

America’s Essential Hospitals, the National Association of Community Health Centers, and others use the Congressional report language to describe program. The American Hospital Association (AHA) stretches the program’s intent:

“The program allows 340B hospitals to stretch limited federal resources to reduce the price of outpatient pharmaceuticals for patients and expand health services to the patients and communities they serve.”

At first, this looks somewhat like the HRSA description, but it distorts the message by including the bit about reducing the price of outpatient pharmaceutical for patients. This programmatic intent is not found in the enacted text, the Congressional report, or in HRSA’s description. It was likely added to look good. But, like in a funhouse, looks can be deceiving. This appears to be a public relations message that, paradoxically, tarnishes the image of covered entities because most savings are, in fact, not used to reduce the price patients pay for drugs. A smarter approach would have kept things simple by describing what the program does — it enables covered entities to obtain lower drug prices.

The critics

PhRMA’s description further distorts the program’s intent:

“The 340B Drug Pricing Program was designed to help patients access more affordable medicines.”

This language is not found in the enacted text. And it is not found in the Congressional report which HRSA leverages and many copy. It does, however, look like a distortion of the AHA’s distorted version. It simultaneously stretches the fabricated portion about reducing the price patients pay for drugs and shrinks — no, eliminates — the portion about expanding health services. It is funny how PhRMA’s description of the program’s intent strays from the intent projected by the Congressional report to argue that the 340B program has “strayed far from its safety net purpose.”

If PhRMA were able to sell members of Congress on a version of intent that is not aligned with how covered entities are using savings (which PhRMA inaccurately describes as “profits”), then PhRMA might help get the votes needed to pass an amendment that, among other things, specifies how savings are to be used and reported. Viewed this way, PhRMA’s description of the program’s intent is, if effective, a clever use of smoke and mirrors to reshape public perception.

A policy funhouse

The 340B legislative intent is not clear. For some, the 340B drug discount program is simply a drug discount program and, as such, is achieving its purpose regardless of how the savings are used. For covered entities, the intent promoted by HRSA can make them look good. But AHA’s distorted intent to look good can backfire and make covered entities look bad. And the intent promoted by PhRMA can make covered entities look bad to grow support for more restrictive amendments.

The ambiguity about legislative intent, particularly regarding the use of program savings, continues to fuel debate about the program’s success and future. Until Congress provides clear guidance on covered entities’ use of savings through an amendment, we’ll likely remain in this policy funhouse, where each stakeholder sees a different reflection of the program’s purpose based on where it stands and which mirror it is facing.

No Comments