Why did the chicken cross the road? To get to the other side. This is an anti-joke where the absence of an expected joke is the surprise factor. But all kidding aside, unless crossing the road was a random act, the chicken crossed the road because it wanted something on the other side. Perhaps it was food, shelter, escape from a threat, or a potential mate. The lower physiological and safety levels of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs likely drove the chicken across the road.

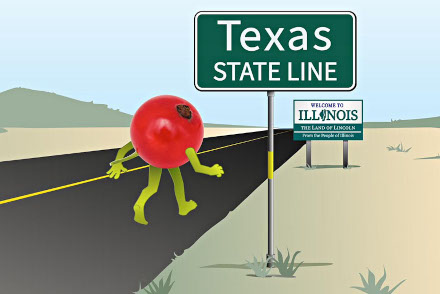

For patients seeking essential health care, crossing boundaries isn’t a punchline — it’s a necessity. Like the chicken seeking basic needs, patients traverse state lines in pursuit of something fundamental: access to medical care. Sometimes it’s for convenience, especially for those living near borders, but increasingly, it’s because lifesaving or essential care simply isn’t available where they live.

The advanced care that drives interstate travel

A study of Medicare beneficiaries with cancer showed that approximately 7% of cancer care was delivered across state lines, and of that, nearly 70% occurred in adjacent states. In this study, interstate travel for care was far more common in rural areas; compared with urban-residing patients, rural-residing patients were 2.5 times more likely to cross state lines for surgical procedures, 3 times more likely to cross state lines for radiation therapy services, and almost 4 times more likely to cross state lines for chemotherapy services. These findings highlight the geographic disparities in access to specialized health care.

Some patients with rare or complex conditions could benefit from or require care available only at centers of excellence (COEs), which are more likely to provide access to experimental treatments through clinical trials. COEs are typically located in major metropolitan areas, and rural patients often cross state lines for care at a COE. Some payers and plan sponsors actively facilitate interstate travel by covering transportation costs to COEs, recognizing the potential for better health outcomes and long-term cost savings.

Laws that drive interstate travel

For many patients, restrictive state policies don’t just create obstacles — they necessitate crossing state lines, sometimes traveling hundreds of miles, to access essential care.

Currant’s analysis of the Guttmacher Institute’s Monthly Abortion Provision Study reveals that about 160,000 patients (approximately 15% of those seeking an abortion) traveled across state lines for one in 2023. Half of these travelers resided in one of the 13 states that, at that time, had near-total or total abortion bans; 40% came from Texas alone. While most sought care in a neighboring state, many traveled significantly further. Illinois became a regional hub — about 40% of the 90,000 abortion patients in Illinois came from out of state.

Abortion bans drive interstate travel and, as intended, they also block access to care. As the Guttmacher Institute notes, those who can neither obtain an abortion in their home state nor travel for an abortion because of financial hardship, disability, fear of repercussions, or other reasons are forced either to remain pregnant or self-manage their care (e.g., by procuring abortion pills by mail).

Increased demand in states protecting access to care could strain resources, potentially leading to longer wait time and limiting provider availability. And providers offering abortion care to patients from states with bans on such care may face legal exposure, including criminal charges, civil lawsuits, and medical license revocation, depending on the laws of the patient’s state of residence. Legal exposure could limit the amount of care providers in sanctuary states are willing to offer.

Some large employers offer travel and lodging benefits for employees needing abortions — very large employers with 5,000 or more employees are more likely to do so. A long list of employers include American Express, Apple, AT&T, Bank of America, Citigroup, CVS Health, Goldman Sachs, Intel, Johnson & Johnson, JPMorgan Chase, Microsoft, Morgan Stanley, Target, and Walt Disney. Most of these policies specify a minimum travel distance (e.g., 100 miles) and some limit coverage to out-of-state services not available in their state of residence. Companies’ motivations range from employee retention to social responsibility.

The barriers to crossing state lines for care

Several significant barriers limit patients’ ability to travel for care:

Financial constraints. Direct travel costs (transportation, meals, accommodations) are often not covered by insurance and typically not extended to caregivers accompanying patients. Indirect costs, such as lost wages, childcare expenses compound the burden. These barriers disproportionately affect low-income and rural residents (who typically face longer travel distances) and patients with chronic conditions requiring ongoing specialized care.

Insurance limitations. Many health plans restrict coverage to in-network providers within specific geographic areas. Non-emergency out-of-network care typically requires preauthorization and often results in treatment delays and higher out-of-pocket costs.

Medical constraints. Some patients simply cannot safely travel due to their medical condition or logistical challenges. Those who have mobility issues, are dependent on difficult-to-transport medical devices, require medications with strict storage requirements, or need access to emergency services often find interstate travel for care impossible rather than just difficult.

Psychological and social challenges. A cancer patient forced to travel for specialized treatment without a caregiver may struggle with social isolation and stress, which can affect recovery. Isolation and stress may be amplified when patients also face language or cultural barriers.

The promise of collaborative-care models

While telemedicine and remote monitoring can reduce the need to travel, in-person care remains essential for many conditions.

For patients with rare or complex care needs, collaborative-care models — where local specialists coordinate with COEs through shared protocols, telehealth, and case reviews — can reduce the need for patients and caregivers to travel. COEs offer advanced diagnostics, personalized treatment plans, and access to clinical trials, while local specialists manage routine monitoring and follow-up care. COEs and local specialists collaborate to coordinate care.

While collaborative-care models can help to improve outcomes, there may be barriers to collaboration including:

- Competition for revenue between COEs and local specialists resulting in a reluctance to share cases

- Licensing restrictions making it harder for out-of-state providers to provide remote care

- Data-sharing challenges

Interstate travel policies at a crossroads

Unlike our chicken from the opening joke, patients don’t cross roads or state lines on a whim. They cross because their lives often depend on care available on the other side. Two critical questions should guide our policies: Why didn’t the patient cross the road? And why did the patient cross state lines?

The answers often reveal uncomfortable truths — financial constraints, insurance limitations, medical constraints, psychological and social challenges, cultural and religious beliefs and, of course, politics — that too often place life-saving care out of reach. And the answers should inform not just how we support interstate travel, but how we reduce the need for it altogether. For those who must travel, support should be as hassle-free as possible. For everyone else, we need solutions that bring care closer to home through collaborative models and telehealth.

It’s time to build bridges instead of barriers — ensuring no life-saving treatment remains a road too far.

No Comments