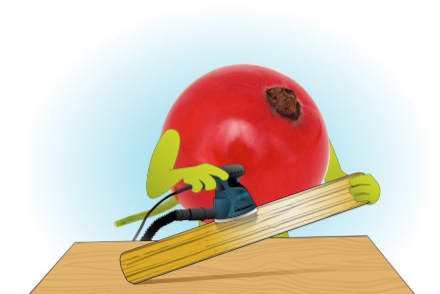

When sanding wood, different grits are used for different purposes: extra-coarse grits to smooth extra-rough and uneven surfaces and to remove paint and varnish; coarse grits to smooth rough and uneven surfaces; medium grits to remove scratches and planning marks; and fine grits for light sanding between finishes. One typically starts with a coarse grit and moves to finer grits in a stepwise fashion.

The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) July 2024 report, “Pharmacy Benefit Managers: The Powerful Middlemen Inflating Drug Costs and Squeezing Main Street Pharmacies,” blames PBMs for driving rebates higher and, consequently, inflating drug costs. Express Scripts sued the FTC on September 17, 2024, demanding that the FTC retract the report. Three days later, the FTC issued a companion administrative complaint against PBMs and group purchasing organizations.

The FTC’s report and complaint are rough around the edges. The FTC inaccurately claims that PBMs inflate drug costs. The truth is our current system, largely based on rebates, inflates the list price of some drugs and subsequently hurts those patients whose coinsurance is tied to the list price of those impacted drugs. To be clear, this is a real problem that needs to be solved. But the FTC’s coarse analysis misplaces blame. It’s time to scratch beneath the surface.

Rebates are not new

PBMs did not invent rebates. Manufacturers have a rich history of offering rebates. Here are just a few examples:

- In 1977, Texas Instruments offered a $10 rebate for the purchase of a SR-56 programmable calculator

- In 1981, Chrysler offered $50 to customers who test-drove a Chrysler car or truck and then bought a comparable vehicle from either Chrysler or a competitor within 30 days of the test drive

- In 1989, Apple offered rebates between $150 and $800 on four of its computers

Manufacturers use rebates to lower the net cost of their products to achieve business objectives, such as boosting sales or growing market share.

Importantly, manufacturers often prefer rebates over discounts or list-price reductions. Manufacturers may use rebates to:

- Facilitate price discrimination

- Maintain perceived value

- Improve short-term cash flow

- Report higher gross sales

- Maintain higher gross margins

- Delay reductions to revenue

Rebates from drug manufacturers are not new

The history of drug rebates begins with manufacturers, which introduced them as a strategic pricing tool. Drug manufacturers began offering rebates in the late 1980s in exchange for coverage or more favorable access versus lowering the price. The Medicaid Prescription Drug Rebate Program (MDRP), established in 1990, helped to expand the use of drug rebates, and the use of rebates in the private sector grew during the 1990s.

The growing demand for rebates from drug manufacturers is a function of a few trends:

- Rising drug costs and the resulting demand for utilization and cost management, including demand for closed formularies with exclusions

- The growth in size and influence of managed care organizations (MCOs) and PBMs — largely from a shift from fee-for-service to managed care, not just mergers — resulting in greater purchasing power

- New products that make some markets more competitive and ripe for restrictions (e.g., step therapy, prior authorization criteria, exclusions) and rebate negotiations

MCOs and PBMs have appropriately negotiated with manufactures to lower the net cost of products, particularly in competitive markets and markets with less-costly alternatives (e.g., insulin). Markets with no competition typically have no rebates — and markets with limited competition or regulatory limits on utilization management (e.g., Medicare Part D protected classes) typically have smaller rebates.

It is crucial to recognize that rebates also benefit some individuals. For example, chief pharmacy officers and employee health benefits managers like rebates because they can easily quantify and report to senior managers the amount they helped the organization “save.”

Rebate guarantees are not new

As the number and size of rebates grew, insurers and self-insured employers increasingly depended on these rebates and wanted predictable savings. In response, PBMs began to offer rebate guarantees in the 1990s. Demand for rebate guarantees grew during the following decade, especially with the rise of Medicare prescription-drug plans, and guarantees had become dominant by the 2010s.

PBMs offer rebate guarantees (and benefit designs, such as coinsurance and closed formularies with exclusions) in response to market demands, not as a deliberate effort to shape the market. They are order takers, not order makers.

Importantly, the big three PBMs offer low-net-cost formularies that do not attempt to maximize rebate revenue and do not offer rebate guarantees, but demand for these formulary products is quite low. Low-net-cost formularies may be a winning long-term strategy, but high member churn and short-term cost pressures often encourages or requires payers to have a short-term focus. PBMs are not to blame for low uptake of low-net-cost formularies.

Blaming PBMs is in vogue and counterproductive

So, who and what is to blame? The manufacturers supplying rebates? The self-insured employers and insurers demanding rebates? The chief pharmacy officers and health benefits managers incented to deliver rebates? The consultants helping plan sponsors maximize rebates? Rising drug costs? New products and increasingly competitive markets? Blaming PBMs is political or ideological — or rational if one simply does not want to go against the grain.

The FTC should not sand off important details when trying to understand the root causes of the problem and assign blame. Its misguided grit to blame PBMs is abrasive to those who have a finer, nuanced understanding of the complexity and dynamics of our current system, including its vicious cycles.

Blaming PBMs is not a productive way to smooth out deeply ingrained problems. The blame game only impedes progress towards meaningful solutions. We need stronger evidence, more value-based payments, greater price transparency, incentives (e.g., tax incentives, public praise) for adopting low-net-cost formularies, a large, long-term demonstration project for a health care savings ledger that may help break plan sponsors’ addiction to rebates, and less finger-pointing.

No Comments