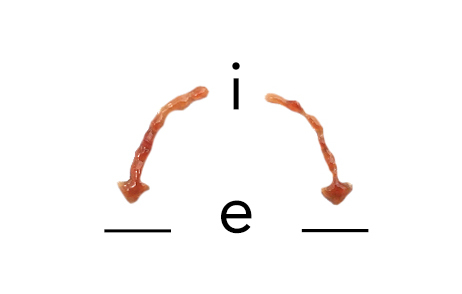

You’re probably familiar with the mnemonic “I before E, except after C” which couples both a spelling rule and an exception to the rule. Most rules have exceptions, and formulary and medical policy rules are no exception. Payers embrace both rules and exceptions because doing so is efficient — one of many words that are exceptions to the “except after C” spelling rule exception.

Some rules are made to be broken

Access to drugs is managed through tiers and restrictions, such as step therapy requirements, prior authorization criteria, and quantity and duration limits. Payers efficiently develop, modify, communicate, and enforce these rules.

When a provider’s request for an exception breaks a rule, a pharmacist or pharmacy tech issues a denial. Some payers give providers an opportunity to make a compelling case through a peer-to-peer review. If the payer upholds the denial and the provider appeals it, then a medical director conducts an internal review. When in doubt, the medical director can reach out to a specialist for guidance. If the medical director upholds the denial, then the appeal can be sent out for an external review by an independent third party upon request. Whereas the initial reviews by pharmacy staff that result in denials are digital in nature with yes/no assessments, the subsequent reviews by medical staff are analog in nature with nuanced assessments.

Exceptions to rules

Payers use exceptions as efficient escape hatches from rules that do not apply to particular cases. Sometimes, a rule may require use of a drug that is contraindicated for a patient. Sometimes, a rule may require use of a drug that a patient previously tried and failed (e.g., an inadequate response, intolerance, or an adverse event). Sometimes, a patient has special requirements (e.g., a special formulation or dosage) that do not conform to the standard rules. Sometimes, switching a patient who is stable on a drug to another drug to abide by a new rule poses too much risk, and the old rule is grandfathered for patients already on therapy. Payers readily acknowledge the importance of exceptions.

Exceptions as a check on rules

Payers create new rules when rates of exceptions or denials overturned upon appeal are high, both of which drive up the cost of enforcement. Enforcement of rules is typically efficient, and when enforcement is no longer efficient — when the costs outweigh (another one of the exceptional words) the benefits — rules are added, modified, or dropped. Payers regularly make exceptions, but exceptions should not be the norm. When exceptions become common, the rule is changed because an inefficient rule is too costly to enforce. For example, the needs of subpopulations may become clear only after launch and as real-world evidence emerges, yet the initial rule may not have anticipated these needs.

Rules are cumbersome if they are exhaustive and describe each and every exception, and they are less effective if they do not address more common cases. Payers continuously attempt to balance rules and exceptions.

When exceptions are unexceptional

Payers routinely grant exceptions on a case-by-case basis, and the ease of obtaining an exception varies by context. Requests for exceptions that are less costly typically encounter less resistance. Payers are more likely to turn a blind eye to the rule when the condition is rare, there are few or no other treatment options, medical necessity is very high, or when the risk of litigation is high.

Requests for exceptions that are evidence-based encounter little to no resistance, even for off-label use. Payers weigh scientific — a couple more words that violate the spelling mnemonic — evidence, such as that in guidelines and peer-reviewed journal articles, when judging the medical necessity of a request.

Exceptions as cover

Exceptions can help to shield payers from criticism and negative PR. When a rule is attacked, a payer can simply point to the exception process as an out. Take an extreme rule: Product X is not covered. Well, even products that are explicitly “not covered” as a general rule are covered when a request for an exception is approved.

Exceptions to the exception process

Whereas rules are transparent and objective, exceptions are more opaque and subjective. This opens the door to variations in how exceptions are granted. Least transparent of all is the call from a self-insured employer’s senior executive informally “requesting” approval for care that would otherwise break the formal rules. The resulting administrative override not only breaks the rules, but circumvents the normal process for making exceptions to the rules.

I before E, except after C

The spelling mnemonic has lots of exceptions, and many of these can be explained by the sound the spelling represents. But its many exceptions call the utility of the rule itself into question. Payers know that formulary and medical policy rules can never be sufficient. Medical judgment is necessary for prescribing decisions on the front end, and the same level of judgment is necessary upon appeal to determine whether a denial should be upheld or overturned on the back end.

Just as the exceptions prove the existence of rules, the rules prove the necessity of exceptions. This duality creates an interesting and important tension.

No Comments